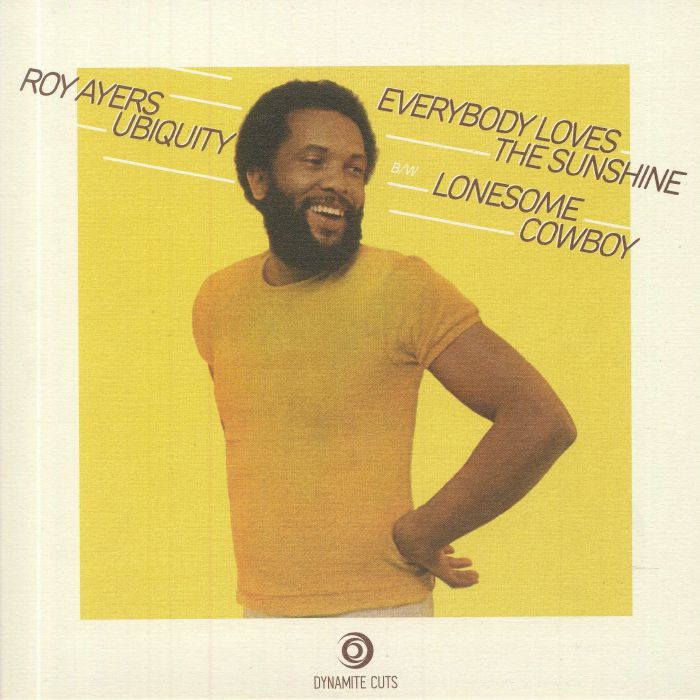

General Midi Karafun Midi for KETRON Midi for Korg Pa1000 Midi for Korg Pa4x Midi for Korg Pa4x Musikant Midi for Korg Pa700 Midi Soft for GENOS Midi Yamaha PSR-SX700 Midi Yamaha PSR-SX900 MP3 Mp3+G Music Soft for KORG Music Soft for ROLAND Music Soft for YAMAHA Music Styles for KORG Music Styles for ROLAND Music Styles for YAMAHA PROF Studio PROF. BUY MIDI: is a piano tutorial showing the basic chords of a Soul classic by the great Roy Ayers. It was also covered by Mary J. Awesome sulltry Japanese only cover version of Roy Ayers annual summer anthem.Essential dubbed out bliss on the flipside.Limited stocks!Second time around for Robert 'Dubwise' Browne's sweet and sweltering reggae cover of Roy Ayers classic 'Everybody Loves The Sunshine', which appeared and disappeared from record stores in double-quick time earlier in the year.

Roy Ayers (born September 10, 1940) is an American funk, soul, and jazz composer, vibraphone player, and music producer. Ayers began his career as a post-bop jazz artist, releasing several albums with Atlantic Records, before his tenure at Polydor Records beginning in the 1970s, during which he helped pioneer jazz-funk. Listen to Everybody-Loves-Somebody.mid, a free MIDI file on BitMidi. Play, download, or share the MIDI song Everybody-Loves-Somebody.mid from your web browser.

Once one of the most visible and winning jazz vibraphonists of the 1960s, then an R&B bandleader in the 1970s and ’80s, Roy Ayers’ reputation s now that of one of the prophets of acid jazz, a man decades ahead of his time. A tune like 1972’s “Move to Groove” by the Roy Ayers Ubiquity has a crackling backbeat that serves as the prototype for the shuffling hip-hop groove that became, shall we say, ubiquitous on acid jazz records; and his relaxed 1976 song “Everybody Loves the Sunshine” has been frequently sampled. Yet Ayers’ own playing has always been rooted in hard bop: crisp, lyrical, rhythmically resilient. His own reaction to being canonized by the hip-hop crowd as the “Icon Man” is tempered with the detachment of a survivor in a rough business. “I’m having fun laughing with it,” he has said. “I don’t mind what they call me, that’s what people do in this industry.”

Growing up in a musical family — his father played trombone, his mother taught him the piano — the five-year-old Ayers was given a set of vibe mallets by Lionel Hampton, but didn’t start on the instrument until he was 17. He got involved in the West Coast jazz scene in his early 20s, recording with Curtis Amy (1962), Jack Wilson (1963-1967), and the Gerald Wilson Orchestra (1965-1966); and playing with Teddy Edwards, Chico Hamilton, Hampton Hawes and Phineas Newborn. A session with Herbie Mann at the Lighthouse in Hermosa Beach led to a four-year gig with the versatile flutist (1966-1970), an experience that gave Ayers tremendous exposure and opened his ears to styles of music other than the bebop that he had grown up with.

Memphis Underground

After being featured prominently on Mann’s hit Memphis Underground album and recording three solo albums for Atlantic under Mann’s supervision, Ayers left the group in 1970 to form the Roy Ayers Ubiquity, which recorded several albums for Polydor and featured such players as Sonny Fortune, Billy Cobham, Omar Hakim, and Alphonse Mouzon. An R&B-jazz-rock band influenced by electric Miles Davis and the Herbie Hancock Sextet at first, the Ubiquity gradually shed its jazz component in favor of R&B/funk and disco. Though Ayers’ pop records were commercially successful, with several charted singles on the R&B charts for Polydor and Columbia, they became increasingly, perhaps correspondingly, devoid of musical interest.

Jazzmatazz, Vol. 1

In the 1980s, besides leading his bands and recording, Ayers collaborated with Nigerian musician Fela Anikulapo-Kuti, formed Uno Melodic Records, and produced and/or co-wrote several recordings for various artists. As the merger of hip-hop and jazz took hold in the early ’90s, Ayers made a guest appearance on Guru’s seminal Jazzmatazz album in 1993 and played at New York clubs with Guru and Donald Byrd. Though most of his solo records had been out of print for years, Verve issued a two-CD anthology of his work with Ubiquity and the first U.S. release of a live gig at the 1972 Montreux Jazz Festival; the latter finds the group playing excellent straight-ahead jazz, as well as jazz-rock and R&B.

allmusic.com

Ayers performing at Glastonbury Festival, 2019 | |

| Background information | |

|---|---|

| Born | September 10, 1940 (age 80) Los Angeles, California, U.S. |

| Genres | Jazz, jazz-fusion, funk, acid jazz, disco, soul jazz, R&B, house, hip hop |

| Occupation(s) | Musician, songwriter, film scorer |

| Instruments | Vocals, vibraphone, keyboards |

| Years active | 1962–present |

| Labels | Atlantic, Polydor, Ichiban, Golden Mink, Nature Sounds, Columbia |

| Associated acts | RAMP, Roy Ayers Ubiquity, Fela Kuti, Tyler The Creator, Edwin Birdsong |

| Website | Official website |

Roy Ayers (born September 10, 1940) is an American funk, soul, and jazz composer, vibraphone player, and music producer.[1] Ayers began his career as a post-bop jazz artist, releasing several albums with Atlantic Records, before his tenure at Polydor Records beginning in the 1970s, during which he helped pioneer jazz-funk.[2] He is a key figure in the acid jazz movement,[3] and has been dubbed 'The Godfather of Neo Soul'.[4] He is best known for his compositions 'Everybody Loves the Sunshine', 'Searchin', and 'Running Away'.[5] At one time, he was said to have more sampled hits by rappers than any other artist.[6]

Biography[edit]

Early life[edit]

Ayers was born on September 10, 1940 in Los Angeles. He grew up in a musical family, where his father played trombone and his mother played piano.[7][8] At the age of five, he was given his first pair of vibraphone mallets by Lionel Hampton. The area of Los Angeles that Ayers grew up in, South Park (later known as South Central) was at the center of the Southern CaliforniaBlack music scene. The schools he attended (Wadsworth Elementary, Nevins Middle School, and Thomas Jefferson High School) were all close to the famed Central Avenue, Los Angeles' equivalent of Harlem's Lenox Avenue and Chicago's State Street. Roy would likely have been exposed to music as it not only emanated from the many nightclubs and bars in the area, but also poured out of many of the homes where the musicians who kept the scene alive lived in and around Central. During high school, Ayers sang in the church choir[9] and fronted a band named The Latin Lyrics, in which he played steel guitar and piano.[10] His high school, Thomas Jefferson High School, produced various talented musicians, such as Dexter Gordon.

Career[edit]

Ayers started recording as a bebop sideman in 1962 and rose to prominence when he dropped out of City College[11] and joined jazz flutist Herbie Mann in 1966.[12]

In the early-1970s, Roy Ayers started his own band called Roy Ayers Ubiquity, a name he chose because ubiquity means a state of being everywhere at the same time.[13]

Ayers was responsible for the highly regarded soundtrack to Jack Hill's 1973 blaxploitation film Coffy, which starred Pam Grier. He later moved from a jazz-funk sound to R&B, as seen on Mystic Voyage, which featured the songs 'Evolution' and the underground disco hit 'Brother Green (The Disco King)', as well as the title track from his 1976 album Everybody Loves the Sunshine.

In 1977, Ayers produced an album by the group RAMP, Come into Knowledge. That fall, he had his biggest hit with 'Running Away'.

In late 1979, Ayers scored his only top ten single on Billboard'sHot Disco/Dance chart with 'Don't Stop The Feeling', which was also the leadoff single from his 1980 album No Stranger to Love, whose title track was sampled in Jill Scott's 2001 song 'Watching Me' from her debut album Who Is Jill Scott?

In the late-1970s, Ayers toured in Nigeria for six weeks with AfrobeatpioneerFela Kuti, one of the African continent's most recognizable musicians.[14] In 1980, Phonodisk released Music of Many Colors in Nigeria, featuring one side led by Ayers' group and the other led by Africa '70.[7][15]

In 1981, Ayers produced an album with the singer Sylvia Striplin, Give Me Your Love (Uno Melodic Records, 1981).[7] In the same year, 1981, he also produced a second album called Africa, Center of the World on Polydor records along with James Bedford and Ayers's bass player William Henry Allen. Allen can be heard talking to his daughter on the track 'Intro/The River Niger'. The album was recorded at the Sigma Sound Studios, New York.

Ayers performed a solo on John 'Jellybean' Benitez's production of Whitney Houston's 'Love Will Save The Day' from her second multi-Platinum studio album Whitney. The single was released in July 1988 by Arista Records.

Ayers has played his live act for millions of people across the globe, including Japan, Australia, England and other parts of Europe.[16]

Ayers is known for helping to popularize feel good music in the 1970s, stating that 'I like that happy feeling all of the time, so that ingredient is still there. I try to generate that because it's the natural way I am'.[17] The types of music that he used to do this consisted of funk, salsa, jazz, rock, soul and rap.[18]

1990s to present[edit]

In 1992, Ayers released two albums, Drive and Wake Up, for the hip-hop label Ichiban Records.[7] and also collaborated with Rick James for an album and is quoted to have been a very close friend of his.[19]

Everybody Loves The Sunshine Midi File

In 1993, he appeared on the record Guru's Jazzmatazz Vol.1 featuring on the vibraphone in the song 'Take a Look (At Yourself)' and the following year appeared on the Red Hot Organization's compilation album Stolen Moments: Red Hot + Cool. The album, meant to raise awareness and funds in support of the AIDS epidemic in relation to the African-American community, was heralded as 'Album of the Year' by Time Magazine.

During the 2000s and 2010s, Ayers ventured into house music, collaborating with such stalwarts of the genre as Masters at Work and Kerri Chandler.

Ayers started two record labels, Uno Melodic and Gold Mink Records. The first released several LPs, including Sylvia Striplin's, while the second folded after a few singles.[7]

In 2004, Ayers put out a collection of unreleased recordings called Virgin Ubiquity: Unreleased recordings 1976–1981 which allowed fans to hear cuts that didn't make it onto the classic Polydor albums from his more popular years.[20]

He has also worked in collaborations with soul songstress Erykah Badu and other artists on his 2004 album Mahogany Vibes.[21]

Roy Ayers hosts the fictitious radio station 'Fusion FM' in Grand Theft Auto IV (2008).

In 2015, he appeared on Tyler, The Creator's album Cherry Bomb on the track 'Find Your Wings'.[22]

Awards and influence[edit]

A documentary the Roy Ayers Project featuring Ayers and a number hip hop producers who have sampled his music and other people who have been influenced by him and his music has been in development for a number of years.[23]

Everybody Loves The Sunshine Midi Free

Pharrell Williams cites Roy Ayers as one of his key musical heroes.[24]

Ayers is a recipient of the Congress of Racial Equality Lifetime Achievement Award.[25]

Discography[edit]

As leader[edit]

- West Coast Vibes (United Artists, 1963)

- Virgo Vibes (Atlantic, 1967)

- Stoned Soul Picnic (Atlantic, 1968)

- Daddy Bug (Atlantic, 1969)

- All Blues (Columbia, 1969)

- Unchain My Heart (Columbia, 1970)

- Ubiquity (Polydor, 1970)

- Live at the Montreux Jazz Festival (Polydor, 1972)

- He's Coming (Polydor, 1972)

- Virgo Red (Polydor, 1973)

- Red Black & Green (Polydor, 1973)

- Coffy (1973)

- Change Up the Groove (Polydor, 1974)

- Mystic Voyage (Polydor, 1975)

- A Tear to a Smile (Polydor, 1975)

- Daddy Bug & Friends (Atlantic, 1976)

- Everybody Loves the Sunshine (Polydor, 1976)

- Vibrations (Polydor, 1976)

- Lifeline (Polydor, 1977)

- You Send Me (Polydor, 1978)

- Step in to Our Life (Polydor, 1978)

- Starbooty (Elektra, 1978)

- Let's Do It (Polydo, 1978)

- Fever (Polydor, 1979)

- No Stranger to Love (Polydor, 1979)

- Love Fantasy (Polydor, 1980)

- Africa, Center of the World (Polydor, 1981)

- Feeling Good (Polydor, 1982)

- Lots of Love (Uno Melodic, 1983)

- In the Dark (Columbia, 1984)

- You Might Be Surprised (Columbia, 1985)

- I'm the One (Columbia, 1987)

- Drive (Ichiban, 1988)

- Wake Up (Ichiban, 1989)

- Searchin' (Jazz House, 1991)

- Hot (Jazz House, 1992)

- Good Vibrations (Jazz House, 1993)

- The Essential Groove Live (Jazz House, 1994)

- Mahogany Vibe (Rapster, 2004)

As sideman[edit]

With Curtis Amy

- Way Down (Pacific Jazz, 1962)

- Tippin' on Through (Pacific Jazz, 1962)

- Katanga! (Pacific Jazz, 1998)

With Herbie Mann

- A Mann & a Woman (Atlantic, 1966)

- The Wailing Dervishes (Atlantic, 1967)

- The Beat Goes On (Atlantic, 1967)

- Impressions of the Middle East (Atlantic, 1967)

- Glory of Love (A&M, 1967)

- Windows Opened (Atlantic, 1968)

- Concerto Grosso in D Blues (Atlantic, 1969)

- Live at the Whisky a Go Go (Atlantic, 1969)

- Memphis Underground (Atlantic, 1969)

- Stone Flute (Embryo, 1970)

- Muscle Shoals Nitty Gritty (Embryo, 1970)

- Memphis Two-Step (Embryo, 1971)

- The Evolution of Mann (Atlantic, 1972)

- Sunbelt (Atlantic, 1978)

- Deep Pocket (Kokopelli, 1992)

With Jack Wilson

- The Jack Wilson Quartet (Atlantic, 1963)

- Plays Brazilian Mancini (Vault, 1965)

- Ramblin' (Vault, 1966)

- Something Personal (Blue Note, 1967)

- Call Me: Jazz from the Penthouse (Century, 2018)

With others

- 4Hero, Creating Patterns (Talkin' Loud, 2001)

- Amerie, Touch (Columbia/Sony, 2005)

- Erykah Badu, Mama's Gun (Motown, 2000)

- Christophe Beck, Ant-Man (Hollywood, 2015)

- Eric Benet, A Day in the Life (Warner Bros., 1999)

- Mary J. Blige, Share My World (MCA, 1997)

- Zachary Breaux, Groovin (NYC 1992)

- Brooklyn Funk Essentials, Stay Good (Dorado, 2019)

- Jean Carn, Trust Me (Motown, 1982)

- Coolio, It Takes a Thief (Tommy Boy 1994)

- Cookie Crew, Fade to Black (1991)

- Digable Planets, Blowout (EMI, 1994)

- Doldinger, Doldinger in New York (WEA, 1994)

- Will Downing, After Tonight (Peak, 2007)

- Ronnie Foster, Love Satellite (CBS, 1978)

- Funkdoobiest, Brothas Doobie (Music On Vinyl, 2016)

- Stu Gardner, Music from the Bill Cosby Show Vol II (Columbia, 1987)

- Ghostface Killah, Apollo Kids (Def Jam, 2010)

- Wolfgang Haffner, Urban Life (Skip, 2001)

- Whitney Houston, Whitney (Arista, 1987)

- Rick James, Throwin' Down (Gordy, 1982)

- Mark James, Mark James (Bell, 1973)

- Miles Jaye, Miles (Island, 1987)

- Miles Jaye, Let's Start Over (4th & Broadway, 1987)

- Jazz Crusaders, Happy Again (Sin-Drome, 1995)

- Jazz Crusaders, Soul Axess (True Life, 2004)

- DJ Jazzy Jeff & The Fresh Prince, Code Red (Jive, 1993)

- Jellybean, Spillin' the Beans (Atlantic, 1991)

- Jeru the Damaja, The Sun Rises in the East (Payday, 1994)

- Ronny Jordan, A Brighter Day (Blue Note, 2000)

- Alicia Keys, Here (RCA, 2016)

- Fela Kuti & Roy Ayers, Music of Many Colours (Phonodisk, 1980)

- Talib Kweli, Eardrum (Warner Bros., 2007)

- Gerald Levert, The G Spot (Elektra, 2002)

- David Linx, Hungry Voices (Miracle, 1989)

- Marley Marl, Re-Entry (BBE 2001)

- James Moody, Moody's Party Live at the Blue Note (Telarc, 1995)

- Mos Def, Black On Both Sides (Rawkus1999)

- Najee, Embrace (N-Coded, 2003)

- David 'Fathead' Newman, Lonely Avenue (Atlantic, 1972)

- David 'Fathead' Newman, Newmanism (Atlantic, 1974)

- Vi Redd, Birdcall (United Artists, 1962)

- Pete Rock & C.L. Smooth, The Main Ingredient (Traffic 2011)

- Jill Scott, Who Is Jill Scott? (Hidden Beach 2000)

- Sandra St. Victor, Gemini: Both Sides (Expansion, 2001)

- Joseph Tawadros, Chameleons of the White Shadow (ABC Music 2013)

- James Taylor Quartet, Room at the Top (Sanctuary, 2002)

- Tony Touch, The Piece Maker 2 (Koch, 2004)

- A Tribe Called Quest, People's Instinctive Travels and the Paths of Rhythm (Sony, 2015)

- Tyler, the Creator, Cherry Bomb (Odd Future, 2015)

- Leroy Vinnegar, Leroy Walks Again!! (Contemporary, 1963)

- Buster Williams, Crystal Reflections (Muse, 1976)

- Vanessa Williams, The Sweetest Days (Mercury, 1994)

- Gerald Wilson, On Stage (Pacific Jazz, 1965)

- Gerald Wilson, The Golden Sword (Pacific Jazz, 1966)

- Jody Watley, I Love to Love (MAW, 2000)

- Jody Watley, Midnight Lounge (Shanachie, 2003)

References[edit]

- ^Cook, Richard (2005). Richard Cook's Jazz Encyclopedia. London: Penguin Books. p. 25. ISBN0-141-00646-3.

- ^'The official website'. Roy Ayers. September 10, 1940. Retrieved September 25, 2012.

- ^Miller, Mark. 'Jazz Review Roy Ayers: Jazz with a Soul Vibe.' The Globe and Mail January 1, 1997: C.3. Print.

- ^Fordham, John. 'The Guide: Music: Roy Ayers Brecon, London.' The Guardian January 1, 2012: 27. Print.

- ^Muhammad, Larry. 'Roy Ayers Still Has Right Vibes.' Courier January 1, 2008: W.11. Print.

- ^Mitter, Siddartha. 'STILL UBIQUITOUS ; WITH HIS JAZZY SOUL AND WONDERFUL VIBES, '70S STAR ROY AYERS IS MUCH IN DEMAND.' BOSTON GLOBE January 1, 2005: D.14. Print.

- ^ abcdeGinell, Richard S. (September 10, 1940). 'Allmusic biography'. Allmusic.com. Retrieved September 25, 2012.

- ^Ratner, Jonathan. 'To Put on Ayers Is Still Divine: Pioneering Vibe-ist on Tour with His Funky All-stars.' National Post January 1, 2006: AL4. Print.

- ^Maxwell, Michele. 'Roy Ayers: A Musical Perfectionist.' Hyde Park Citizen Jan. 1, 2000: 24. Print.

- ^Nichol, Alan. 'Ayers Rocks.' Evening Chronicle January 1, 2005, 01B ed.: 2. Print.

- ^Shuler, Deardra. 'Roy Ayers Sampled by Major Hip Hop Artists.' New York Beacon January 1, 2006: 28. Print.

- ^Massimo, Rick. 'The Sound of Music – Roy Ayers Has That Jazz Vibe Going:.' The Providence Journal January 1, 2005: F.23. Print.

- ^Shuler, Deardra. 'Roy Ayers: Everybody Loves His 'Sunshine' New York Amsterdam News1 Jan. 2010: 23. Print.

- ^No Author. 'An Open Letter from Roy Ayers.' The Indianapolis Recorder January 1, 1980: 10. Print.

- ^'Fela Anikulapo Kuti* And Roy Ayers - Music Of Many Colours'. Discogs. Retrieved February 16, 2016.

- ^Thomas, Don. 'Roy Ayers Is Definitely Lyrically Correct With 'Spoken Word' New York Beacon January 1, 1998: 26. Print.

- ^White, Tony. 'Warm Vibes Flow in the Sunshine of Roy Ayers.' American Red Star January 1, 1998: B.9. Print.

- ^Thomas, Don. 'Vibist Roy Ayers: As Jazzy As Ever.' New York Beacon Jan. 1, 1995: 27. Print.

- ^Siobhan, Kane. 'No Wonder Everyone Wants to Sample the Great Vibes of Roy Ayers: Ayers Is Pivotal in Funk and Jazz, and Has Stories of Working with Fela Kuti and Rick James.' Irish Times January 1, 2014: 13. Print.

- ^Richens, Mark. 'COLLECTION OF UNRELEASED RECORDINGS FROM AYERS PROVES HIS VIBE MASTERY.' The Commercial Appeal Jan. 1, 2004: G30. Print.

- ^Williams, Damon C (October 5, 2004). 'Father of fusion Roy Ayers connects with the stars on latest album'. Knight Ridder/Tribune News Service. Archived from the original on April 17, 2018. Retrieved April 16, 2018.

- ^'Tyler, The Creator Interview w/ Bootleg Kev 'Fuck Target', Bruce Jenner, & More'. YouTube. April 16, 2015. Retrieved July 28, 2016.

- ^Jackson, Nate. 'Roy Ayers: Man of the Mallet and the Moment.' Los Angeles Times January 1, 2011: D.10. Print.

- ^Butler, Kate. 'Roy Ayers: [Final 5 Edition].' Sunday Times January 1, 2004: 39. Print.

- ^No Author. 'Jazz Great Roy Ayers to Perform at PJC.' Pensacola News Journal January 1, 2006: B.1. Print.

External links[edit]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Roy Ayers. |

- Documentary Film of Roy Ayers